There’s something wonderfully paradoxical about experiencing the Venice Architecture Biennale—this exhibition of radical futures unfolding within one of the world’s most preciously preserved historical environments. Venice itself seems to exist in defiance of rational urban planning, a labyrinthine dream-city built on water, its foundations driven into lagoon mud centuries before modern engineering. Yet here, in its Arsenal and Giardini, architects and designers from across the globe gather to reimagine the built environment for coming decades and centuries.

I spent yesterday wandering through pavilions that blur the boundary between the possible and the fantastical. This year’s Biennale theme, “The Laboratory of the Future,” has produced installations that function simultaneously as speculation, critique, and technical proposition. Many exhibits explore the intersection of environmental crisis and human habitation—floating communities designed to rise with sea levels, vertical farms integrated into urban housing, building materials that metabolize carbon dioxide rather than producing it.

What strikes me most is how these architectural visions represent a hybrid of reality and imagination—projections grounded in material possibility yet liberated from current constraints. This balance feels intimately familiar, as it mirrors what I’ve been attempting in “Shattered Horizons of Tarveran,” where the fictional metropolis exists just beyond the edge of the plausible.

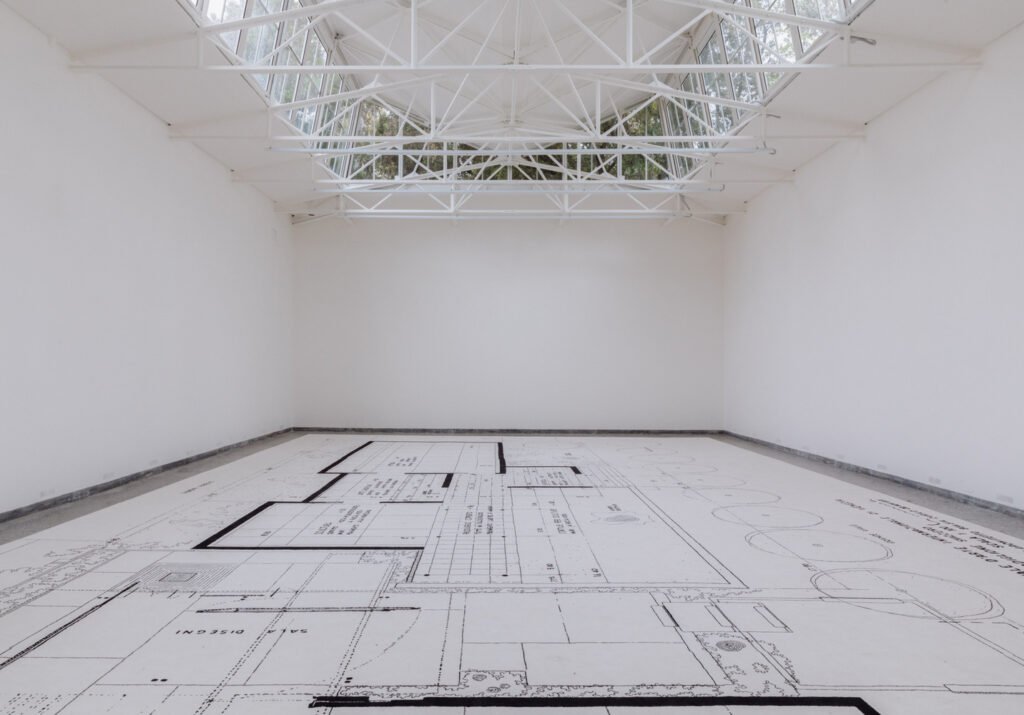

The Swiss pavilion particularly captured my attention with its exploration of “permeable boundaries”—structures designed to intentionally blur distinctions between interior and exterior, private and public, human-made and natural. The centerpiece installation features walls that gradually transform from solid concrete to increasingly porous screens, finally dissolving into a lattice so open it barely constitutes a barrier at all. Climbing plants weave through the structure, further complicating the distinction between architecture and environment.

This aesthetic of dissolution and interpenetration immediately brought to mind the shifting reality of Tarveran, where physical laws themselves have begun to weaken, creating zones where conventional boundaries fail. Working on the novel, I’ve been developing architectural language to convey this instability. Standing in the Swiss pavilion, I found unexpected validation for descriptive approaches I’d been unsure about—seeing physically manifested what I’d been attempting to capture in prose.

The Korean pavilion offered another resonant experience with its focus on “adaptive reuse”—the transformation of existing structures for new purposes rather than demolition and reconstruction. Their exhibition showed a decades-long evolution of a single industrial complex through multiple repurposings, each adaptation leaving traces of previous iterations visible. This palimpsest approach to architecture, where history remains legible beneath new interventions, aligns perfectly with how I’ve imagined Tarveran’s corporate district—a zone where buildings bear visible evidence of their transformations through time.

In my notebook, I revisited a passage describing one of Tarveran’s central structures, refining it based on details observed in the exhibition:

The Nexus Tower dominated the financial district, its lower thirty floors reflecting architectural conventions from the previous century—solid, rectangular, assertively vertical. Above this base, however, the structure underwent a radical transformation. The upper levels expanded outward in organic-seeming protrusions, their surfaces alternating between reflective glass and photosensitive membranes that adjusted their transparency according to sunlight intensity.

These newer portions seemed to defy conventional structural logic, cantilevering improbably far from the building’s core. From certain angles, they appeared almost disconnected from the main tower, floating independently in midair. This visual paradox resulted from the integration of almost invisible tensile supports and the strategic use of gradient materials that became increasingly transparent along their length.

Most distinctive was the central atrium that pierced the entire height of the building, transforming from a conventional skylight at the lowest levels into something far more ambiguous near the summit. Here, the boundary between interior and exterior blurred completely. Weather systems sometimes formed in this upper space—small clouds condensing around climate control emissions, occasional light precipitation falling through the building’s core to collection basins thirty floors below.

Employees spoke of the tower as an entity with moods and preferences—areas that felt welcoming or hostile on particular days with no discernible pattern. Some avoided the transition zones, where older and newer architecture met, citing unexplained discomfort. Others sought these thresholds out, claiming enhanced creativity and unexpected insights while working in these liminal spaces.

Walking among the Biennale’s physical models and immersive installations, I’m struck by how architectural imagination serves as a particularly useful bridge between the literal and the figurative. These speculative structures simultaneously address practical concerns (How might we live? How might we build?) and metaphysical ones (What constitutes a boundary? How do we define inside and outside? What is the relationship between form and function?).

This dual capacity—to be both pragmatically grounded and philosophically expansive—is what I aspire to in my own writing. In “Shattered Horizons of Tarveran,” the physical fracturing of space serves as both plot mechanism and metaphorical framework for exploring how certainties crumble, how fixed boundaries become permeable, how we navigate when fundamental assumptions fail.

As I leave Venice tomorrow, I carry with me not just specific visual inspirations but a deepened conviction about the value of disciplinary cross-pollination. Engaging with architectural thinking has clarified certain narrative challenges I’ve been wrestling with—particularly how to make abstraction concrete, how to physicalize philosophical concepts, how to create settings that function simultaneously as backdrop and active agent in the story.

“Architecture is the reaching out for the truth.” (Louis Kahn’s observation resonates particularly after experiencing the Biennale’s ambitious attempts to manifest possible futures in present form)